Efficacy and safety of sequential neoadjuvant chemotherapy and short-course radiation therapy followed by delayed surgery in locally advanced rectal cancer: a single-arm phase II clinical trial with subgroup analysis between the older and young patients

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study was performed to investigate the efficacy and safety of short-course radiation therapy (SCRT) and sequential chemotherapy followed by delayed surgery in locally advancer rectal cancer with subgroup analysis between the older and young patients.

Materials and Methods

In this single-arm phase II clinical trial, eligible patients with locally advanced rectal cancer (T3–4 and/or N1–2) were enrolled. All the patients received a median three sequential cycles of neoadjuvant CAPEOX (capecitabine + oxaliplatin) chemotherapy. A total dose of 25 Gy in five fractions during 1 week was prescribed to the gross tumor and regional lymph nodes. Surgery was performed about 8 weeks following radiotherapy. Pathologic complete response rate (pCR) and grade 3–4 toxicity were compared between older patients (≥65 years) and younger patients (<65 years).

Results

Ninety-six patients with locally advanced rectal cancer were enrolled. There were 32 older patients and 64 younger patients. Overall pCR was 20.8% for all the patients. Older patients achieved similar pCR rate (18.7% vs. 21.8; p = 0.795) compared to younger patients. There was no statistically significance in terms of the tumor and the node downstaging or treatment-related toxicity between older patients and younger ones; however, the rate of sphincter-saving surgery was significantly more frequent in younger patients (73% vs. 53%; p=0.047) compared to older ones. All treatment-related toxicities were manageable and tolerable among older patients.

Conclusion

Neoadjuvant SCRT and sequential chemotherapy followed by delayed surgery was safe and effective in older patients compared to young patients with locally advanced rectal cancer.

Introduction

Rectal cancer is one of the most common cancers of the gastrointestinal tract with a high recurrence and mortality rate. Survival rates for patients with rectal cancer have improved over the past three decades due to early detection in the early stages, a reduction in postoperative mortality and successful treatment in stages I and II of the disease [1]. However, locally advanced rectal cancer remains a challenge because of the high recurrence rate following surgery [2].

Neoadjuvant chemoradiation has been introduced and proven effective to reduce locoregional recurrence of those patients in randomized trials [3]. Radiotherapy can also be used to relieve local tumor symptoms [4]. Many protocols of preoperative chemoradiation were investigated comparing a short course of radiotherapy over a week to a longer course over five weeks [4-12]. The shorter course of radiotherapy was attractive especially for older patients with cancer because it reduced the need for daily transportation and hospital visits especially in light of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Older patients with cancer are at high risk of dying if infected by the virus [13]. However, the safety and efficacy of this shorter course of radiotherapy has not been investigated in older patients with locally advanced cancer. Thus, we conducted this prospective study to investigate the feasibility of short-course radiation therapy (SCRT) in combination with neoadjuvant preoperative chemotherapy for those patients.

Materials and Methods

1. Patient eligibility

In this phase II prospective clinical trial, eligible patients with locally advanced rectal cancer (T3–4 and/or N1–2) were enrolled between 2019 and 2020. Inclusion criteria included all adult patients (≥18 years) with newly diagnosed rectal cancer (up to 15 cm distance from the anal verge); histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma; clinical stage of T3 or T4 and/or N1–2; the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status <2; adequate bone marrow, hepatic, and renal functions.

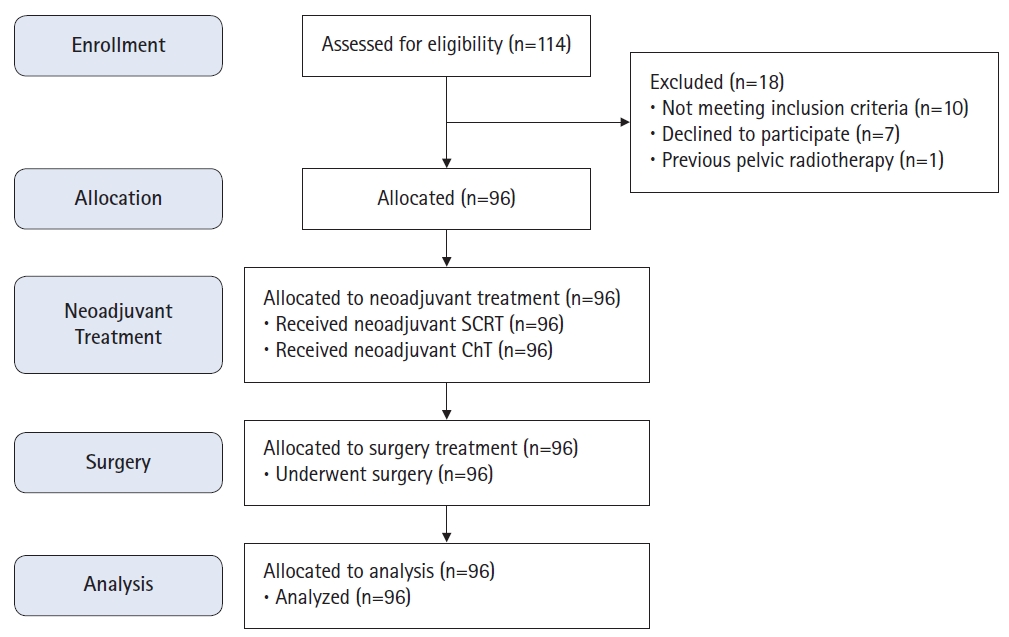

Exclusion criteria included all patients with pregnancy; other primary malignancies; any type of distant metastasis; serious medical conditions (including severe cardiovascular, renal and/or hepatic failure); previous pelvic radiation therapy; hypersensitivity reaction to fluorouracil, oxaliplatin or capecitabine; patients’ refusal to participate in the study (Fig. 1).

2. Preliminary evaluation

Demographic and clinical characteristics of eligible patients such as age, sex, medical and surgical history, and physical examination were recorded using a data collection form. All participants were asked for any history of cardiac, liver, or kidney dysfunction and allergic reactions to the drug. All the patients underwent colonoscopy by a gastroenterologist and the site and characteristics of the tumor and its distance from the anal verge were assessed. The diagnosis of rectal adenocarcinoma was verified by pathologic examination of the biopsy specimen. Before starting treatment, all the patients underwent digital rectal examination (DRE), abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scans, and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Clinical staging of the tumor was performed using TNM classification according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system and completed based on MRI and CT scan images. Performance status was assessed according to ECOG criteria. Complete blood cell count, liver function test, renal function test, electrolytes, and carcinoembryonic antigen was recorded.

3. Treatment

All the patients received a cycle of neoadjuvant chemotherapy before SCRT and two cycles of chemotherapy after SCRT and before surgery. Based on our previous study and literature finding [14], induction chemotherapy can shrink the tumor and alleviate tumor-related symptoms such as pain and bleeding; therefore, this strategy can enhance tumor response and facilitate patients’ compliance. Chemotherapy was administered with either the CAPEOX (capecitabine + oxaliplatin) regimen (80%) or oral capecitabine alone (20%). The CAPEOX regimen consisted of oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 (day 1) followed by oral capecitabine 1,000 mg/m2 PO bid (day 1–14). During COVID-19 pandemic, according to the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guideline adapted treatment recommendation in COVID-19 era, we had to do some modification in chemotherapy regimen to decline the risk of coronavirus infection and its morbidity and mortality. Therefore, most participant particularly older patients received capecitabine alone rather than CAPEOX regimen. Three weeks after the day 1 of the first chemotherapy cycle, all the patients underwent SCRT. Subsequently, 2 weeks after the completion of SCRT, the patients received two more cycles of chemotherapy with the same regimen. Three weeks later, they underwent surgery with an average interval of 8 weeks from the end of neoadjuvant radiation therapy. Fig. 2 shows study protocol diagram.

4. short-course radiation therapy

The patients underwent a CT scan with SOMATOM Definition AS Siemens scanner (Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany), and the images were transferred to the treatment planning system (TPS) through a DICOM network (INFINITT Healthcare, Seoul, Korea). The target volumes were contoured based on the RTOG anorectal contouring atlas [15]. Accordingly, gross tumor volume (GTV) included all primary gross diseases and all visible and suspicious perirectal and iliac nodes. Clinical target volume (CTV) included the GTV plus 1.5–2 cm margin; as well as, the entire rectum, mesorectum, and presacral space. Internal iliac nodes were included in the CTV for all cases; however, external iliac nodes were covered for cases with T4 tumors. Planning target volume (PTV) was created by expanding CTV plus 0.5–1 cm margin. Treatment planning was performed using Prowess Panther software version 5.4 (Prowess Inc., Concord, CA, USA) and the minimum, maximum, and mean doses for target volumes as well as organs-at-risk (OARs) such as the bladder and the right and left femoral heads were evaluated on a dose-volume histogram (DVH). Subsequently, the patients underwent SCRT with a total dose of 25 Gy in 5 fraction within 5 consecutive days with three fields (one posterior field and two lateral fields) or four-field technique (anteroposterior-posteroanterior parallel opposed fields and two lateral opposed fields) for PTV coverage with 95% isodose (according to the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements [ICRU] Report 62 protocol) with 18 MV photon beam using the ONCOR linear accelerator (Siemens Healthcare GmbH). All the patients were treated in a single phase and no boost dose was delivered.

Acute gastrointestinal, urinary and hematologic side effects of radiation therapy were scored according the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Side Effects (CTCAE) version 5.0 (grades 1 to 5) [5].

5. Surgery

A standard radical surgery such as low anterior resection (LAR) or abdominoperineal resection (APR) was performed for all the patients. The type of surgery (APR vs. LAR) was usually selected at diagnosis and before neoadjuvant therapies based on many factors such as tumor location, adequacy of anal sphincter function, and patient choice. However, in some patients whose tumor location was borderline (4–5 cm above anal verge), and unknown sphincter function the choice of surgical technique was postponed until neoadjuvant treatment was completed.

6. Pathologic response evaluation

The postoperative pathological examination provided a microscopic description of the specimen with at least four paraffin blocks and an additional larger block. If no tumor was visible, slides were re-taken from the entire suspected area and a more accurate assessment was performed. Circumferential resection margin was defined as involved if the tumor was microscopically located less than 1 mm from the radial resection margin. Pathologic response was graded based on pathologist evaluation of the sample obtained from surgical resection. Downstaging was defined as any stage reduction following neoadjuvant treatments from stage III to stage 0–II, and stage II to stage 0–I confirmed in the pathological specimens [16]. PCR was defined as the absence of tumor cells at the primary site and lymph nodes. A nonresponsive tumor was defined as less than 30% tumor shrinkage following neoadjuvant treatments [6]. In this study, we used the four AJCC tumor regression grading (TRG) classifications for evaluating. Based on this scoring system, the tumor regression is categorized as complete regression (no viable cancer cells, TRG = 0), near complete regression (residual single or small groups of tumor cells, TRG = 1), moderate regression (residual cancer outgrown by fibrosis, TRG = 2) and finally, minimal or no regression (minimal or no tumor cells killed, TRG = 3) [17].

7. Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was pCR and the secondary endpoint was adverse events. Patients were monitored weekly for acute toxicity and treatment compliance.

8. Statistical analysis

We calculated the study sample size based on the guidance and formula provided by Khan et al [18]. Accordingly, to improve a 10% in pCR in the present study (P1 = 20%) compared to a study by Faria et al. [19] (P0 = 10%), and determined α = 5% (exact α = 4.53%) and power = 80% (exact power = 80.81%), the number of 87 was estimated. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The frequency of the variables was presented by the numbers and percentages. A mean ± standard deviation was used for continuous variables. The normality of data distribution was tested by Kolmogorov-Smirnov. Chi-square test (χ2) was applied to compare the pCR rate among the subgroups, and to compare the severity of treatment-related side effects at different times, Friedman test, and comparison of laboratory parameters in three times of visits, repeated-measures ANOVA were used. The significance level for all tests was considered 0.05.

9. Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences in accordance with the code of ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans (No. IR.SUMS.MED.REC.1397.437). All patients signed informed consents prior to enrollment. The clinical trial was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (No. IRCT20190119042415N1) and all patients’ data have remained confidentially.

Results

1. Participants

Ninety-six patients with rectal cancer underwent SCRT and chemotherapy followed by delayed surgery. Response to treatment was assessed by pathologic examination on postoperative specimens (Fig. 1).

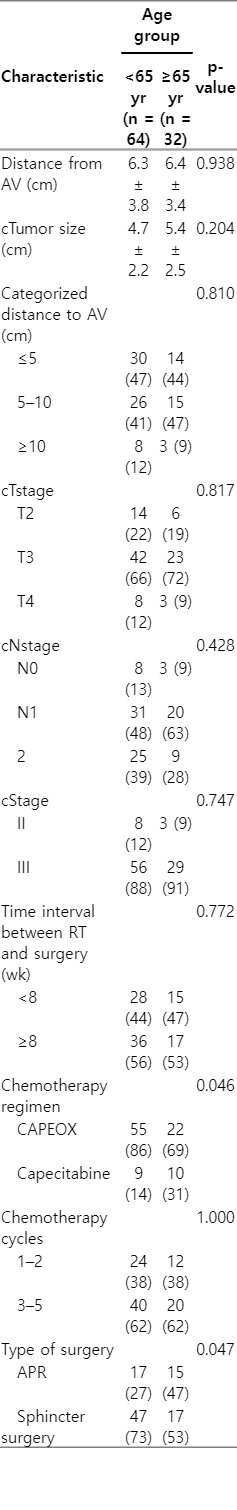

2. Baseline characteristics and treatment

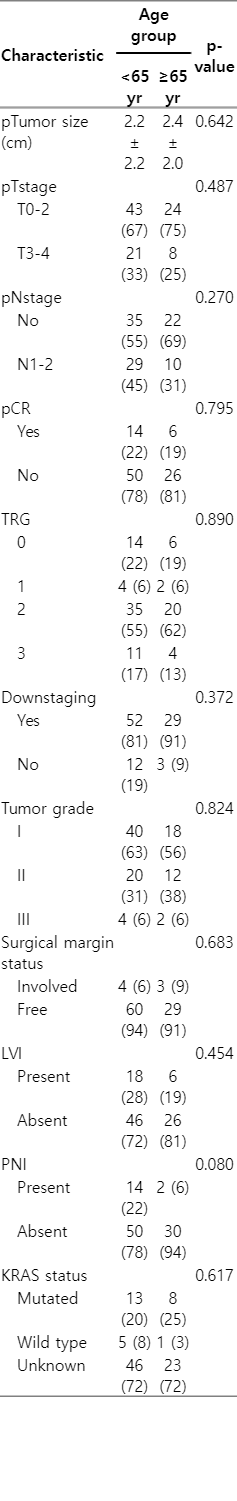

The median age of all patients was 59 years (range, 29 to 97 years). Sixty-four cases (66.7%) were younger than 65 years (median, 53 years), and 32 cases (33.3%) were 65 years or older (median, 75 years). In terms of sex, 59 subjects (64.1%) were male, and 24 subjects (35.9%) were female. All the patients completed their planned SCRT with similar dose, technique and scheduled. The number of chemotherapy cycles in both group was comparable; however, the CAPEOX regimen was more frequently administered in younger patients compared to older patients who were less tolerated oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy (69% vs. 86%; p = 0.046). Table 1 summarizes patient characteristics.

Clinical characteristics of the tumor in patients with rectal cancer underwent SCRT and chemotherapy followed by delayed surgery

Overall, APR was performed for 32 (33%) rectal cancers and LAR in 64 (67%) patients in whom the cancer was close to or involved the anal canal. Sphincter-sparing surgery was more frequent among younger patients compared to the older patients (73% vs. 53%; p = 0.047). The reason of higher rate of APR in older patient was more due to the higher rate of impaired anal sphincter in tonometry or fecal incontinency at diagnosis, as well the patient and the surgeon preference rather than a surgical technique problem. It is believed that older patients have lower quality of life following LAR due to fecal incontinency and higher rate of LAR syndrome compared to younger patients. No serious postoperative side effects such as massive hemorrhage, infection or wound dehiscence, and leakage at the anastomosis site were observed. In terms of delay in surgery, the median time interval between SCRT and surgery was 8 weeks (range, 6 to 12 weeks). This interval was less than 8 weeks in 44 cases (46%), and was more than or equal to 8 weeks in 52 cases (54%). There was no difference regarding the time interval between older and younger patients.

3. Response rates

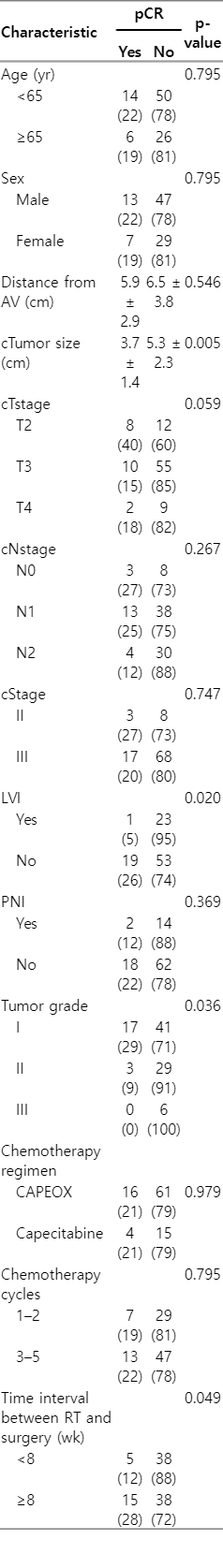

Overall, partial and complete tumor response was seen in 82 patients (85.4%). Evaluation of the primary outcome of the study showed that 20 patients (20.8%) achieved pCR, 62 cases (64.6%) partial pathologic response, and 14 patients (14.6%) were nonresponsive. Table 2 summarizes the pathological response following surgery. There was no statistically significant difference between the younger and older patients in terms of pCR rate (18.7% vs. 21.8%; p = 0.795) and as well as other pathologic characteristics (Table 2). However, the lack of lymphovascular invasion (p = 0.020), lower tumor grade (p = 0.036), larger tumor size (p = 0.005), and the time interval more than 8 weeks between neoadjuvant SCRT and surgery (p = 0.049) was correlated with higher rate of pCR (Table 3).

Distribution and comparison of pathologic characteristics among the older and younger patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated by neoadjuvant SCRT and chemotherapy followed by delayed surgery

4. Adverse events

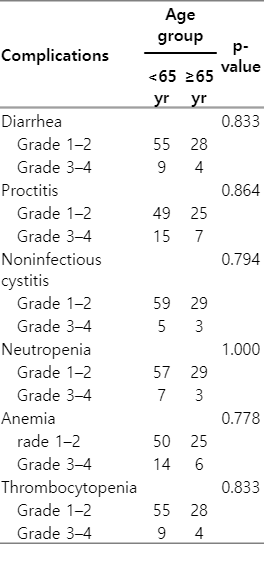

There was no statistically significance in terms of treatment-related side effects including gastrointestinal, urinary and hematologic toxicities between older patients and younger ones (Table 4).

Discussion and Conclusion

Despite the decline in the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer in the last decade, it accounts the second leading cause of death in older patients. Rectal cancer consists of about 30%–40% of all colorectal cancers [20]. Rectal cancer in older patient tends to be missed and diagnosed in locally advanced stage, particularly in developing countries [8,9]. Given the higher rate of underling comorbidities, lower performance status and lower compliance to the treatment, older patients with rectal cancer are frequently undertreated. Therefore, most older patients are spared from many clinical trials and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and only be treated by SCRT or long-course chemoradiation alone. This modified neoadjuvant therapies may cause lower rate of pCR, as well lower survival rates [10].

In the current clinical trial, we hypnotized that the adding sequential chemotherapy with CAPEOX regimen to SCRT is feasible and tolerable in older patients compared to younger ones. The majority (69%) of older patients received and tolerated well a median three cycles of CAPEOX with acceptable toxicity. In addition, another advantage of CAPEOX regimen, particularly in the COVID-19 era is outpatient administration, reduced hospital visit and limited exposure to the coronavirus that may decline the morbidity and mortality related to COVID-19 infection. According to the ESMO guideline, capecitabine alone or combination of capecitabine and oxaliplatin (such as CAPEOX) is suggested as treatment adapted recommendation in the COVID-19 era for the stage III rectal cancer [11].

In the present study, we found a comparable pCR, downstaging rate, R0 resection, and treatment-related toxicity in older patients compared to younger patients; however, sphincter-sparing surgery was more frequent among younger patients compared to the older patients. The reason of higher rate of APR in older patient was more due to the higher rate of impaired anal sphincter in tonometry or fecal incontinency at diagnosis, as well the patient and the surgeon preference rather than a surgical technique problem. It is believed that older patients have lower quality of life after LAR due to fecal incontinency and higher rate of LAR syndrome compared to younger patients [21]. LAR syndrome has been poorly defined as a set of complaints, including fecal frequency, urgency, and incontinency, or a feeling of rectal fullness despite defecation. This syndrome causes a considerable impact on the patient’s quality of life and leads many patients to select a permanent colostomy to prevent these symptoms [22]. In agreement with our results, Partl et al. [23] and Temple et al. [24] found age as an independent predictive factor for sphincter-preserving surgery following neoadjuvant treatments in patients with rectal cancer. They found a higher rate of sphincter-preserving surgery in younger patients compared to older ones.

In the current study, the rate of pCR was 20.8% (20 of 96) for all enrolled patients. This pCR rate is compatible with the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis in which the estimated pooled pCR rate was 17.5% (95% confidence interval, 15.7–19.4) in long-course chemoradiation studies; as well as, 11.8% in SCRT with delay surgery in in the randomized Stockholm III trial [25,26]. In the present study, we found a significantly higher rate of pCR in patients who underwent surgery with a delay time of at least 8 weeks; therefore, it seems that the time interval plays a crucial role in the rate of pCR to neoadjuvant SCRT and this effect will be more remarkable compared to early surgery. Our finding is in consistent with the several reports and systematic review that confirmed the impact of time interval between SCRT, as well as chemoradiation and surgery on the rate of pCR [12]. Previous studies evaluated and confirmed the efficacy and safety of adding induction chemotherapy to chemoradiation in locally advanced rectal cancer [27]; however, there is paucity and very limited data in the literature regarding the feasibility and the safety of neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with SCRT in older patients with rectal cancer [28]. In a phase II clinical study, Aghili et al. [27] showed that the adding concurrent chemotherapy to SCRT and with delay surgery can provide an enhanced pCR (30.8%) with acceptable and manageable toxicity. In another randomized controlled trial, they also showed this treatment strategy could provide similar pCR rate compared to long course chemoradiation [9]. However, a phase 2 multicenter study found short-course concurrent CRT followed by delayed surgery in patients with rectal cancer was associated with poor pCR associated with significant toxicity despite using advanced radiotherapy technique [29]. In a large multicenter randomized clinical trial (RAPIDO), sequential neoadjuvant SCRT and chemotherapy followed by surgery was associated lower disease-related treatment failure compared to standard neoadjuvant long-course chemoradiation followed by surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy [30]. In the current study, we used SCRT with sequential chemotherapy rather than concurrent chemotherapy. This treatment strategy was less toxic particularly in older patients. In addition, by this treatment strategy, we achieved a good pCR and acceptable toxicity comparable with previous reports in which patients were treated by combined neoadjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiation or SCRT [30].

In this clinical trial, we used three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for delivering SCRT; therefore, by using new radiotherapy techniques such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy that provide radiation dose escalation, more improvement in the pCR will be expected.

Facing the COVID-19 pandemic was the most important limitation of the study. Continuation of the study based on the initially designed protocol, particularly potentially life-threatening chemotherapy regimen that could decrease immunity and increase the risk of infection was the main challenging issue in elderly patients. Therefore, we had to change the initial chemotherapy regimen (CAPEOX) to capecitabine alone to decrease social exposure of some older patients.

In conclusion, neoadjuvant SCRT and sequential chemotherapy followed by delayed surgery was safe and effective in older patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. A prospective randomized study should be performed to confirm this hypothesis.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

This clinical trial was approved and supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. The manuscript is part of a thesis by Ali Akbar Hafezi.