Radiotherapy trend in elderly hepatocellular carcinoma: retrospective analysis of patients diagnosed between 2005 and 2017

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

To report the trends of radiotherapy in the management of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed patients who entered HCC registry of Samsung Medical Center between 2005 and 2017. Patients who were 75 years or older at the time of registration were defined as elderly. They were categorized into three groups based on the year of registration. Radiotherapy characteristics were compared between the groups to observe differences by age groups and period of registration.

Results

Out of 9,132 HCC registry patients, elderly comprised 6.2% (566 patients) of the registry, and the proportion increased throughout the study period (from 3.1% to 11.4%). Radiotherapy was administered to 107 patients (18.9%) in elderly group. Radiotherapy utilization in the early treatment process (within 1 year after registration) has rapidly increased from 6.1% to 15.3%. All treatments before 2008 were delivered with two-dimensional or three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy, while more than two-thirds of treatments after 2017 were delivered with advanced techniques such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy, stereotactic body radiotherapy, or proton beam therapy. Overall survival (OS) of elderly was significantly worse than younger patients. However, for patients who received radiotherapy during the initial management (within one month after registration), there was no statistically significant difference in OS between age groups.

Conclusion

The proportion of elderly HCC is increasing. Radiotherapy utilization and adoption of advanced radiotherapy technique showed a consistently increasing trend for the group of patients, indicating that the role of radiotherapy in the management of elderly HCC is expanding.

Introduction

Primary liver cancer is the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. In South Korea, primary liver cancer was the second most common cause of cancer-related death in 2020 and the number one cause of death among people aged 40–59 years [2]. Approximately 75% of all primary liver cancers are hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [3]. The crude incidence rate of HCC in South Korea has slowly decreased over a 10-year period (from 2008 to 2018) [4]. However, the age-standardized incidence rates in those aged ≥80 years have significantly increased [5]. Elderly patients tend to have multiple comorbidities and are considered vulnerable to surgical and/or systemic treatment related complications [6,7]. According to the vital statistics of South Korea, a 75-year-old man in 2020 is expected to live an additional 11.6 years, and a 75-year-old woman in 2020 is expected to live an additional 14.7 years [8], indicating the need for appropriate treatment for elderly patients with HCC. However, while there is a consistent need for appropriate treatment guidelines for elderly patients with HCC due to the above-mentioned issues, there is still a lack of recommendations focusing on these patients [2,9].

Radiotherapy in the management of HCC was limited due to the radiosensitive nature of background normal liver parenchyma [10,11]. However, with advancements in radiotherapy techniques, the role of radiotherapy in the management of HCC has changed dramatically over the last few decades. With the aid of improved image guidance, conformal delivery techniques, and various radiotherapy modalities, radiotherapy for HCC has resulted in high local control rates with relatively low toxicity in multiple clinical trials [12-16].

Though multiple studies report that the role of radiotherapy in the management of HCC is changing [2,13,17] and that radiotherapy is equally safe and effective for elderly patients [18-20], there is a current lack of an overall review of how radiotherapy is administered for the management of elderly patients with HCC in the real world. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to report how radiotherapy utilization for the management of these patients has changed over time.

Materials and Methods

1. Study population

This retrospective study used the prospectively collected registry data of patients with newly diagnosed, previously untreated HCC at Samsung Medical Center. The diagnosis of HCC was confirmed histologically or clinically, based on the guidelines of the Korean Liver Cancer Association-National Cancer Center (KLCA-NCC) [21-23]. The HCC registry collected the baseline clinical characteristics of the patients, including age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, hypertension, diabetes, Child-Pugh classification, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, and initial treatment method. Details of the HCC registry have been previously described [24,25]. The data of patients registered between 2005 and 2017 were used for this study.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (No. 2021-12-093-001). Written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

2. Assessments

We investigated whether radiotherapy was utilized in the subsequent HCC treatment process. Medical records between January 2005 and December 2022 were reviewed. Following radiotherapy characteristics were collected: treatment aim (curative vs. palliative), target lesion (intrahepatic vs. other), radiotherapy timing (during initial management vs. during the treatment course), and radiotherapy technique—two-dimensional radiotherapy (2D-RT) vs. three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) vs. intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) vs. stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) vs. proton beam therapy (PBT). All of the radiotherapy sessions were counted individually if the patient underwent multiple sessions of radiotherapies. SBRT or high-dose irradiation to intrahepatic lesions, and high-dose radiotherapy in addition to transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) were regarded as curative aim radiotherapy. TACE is considered as palliative treatment, and TACE plus radiotherapy is also generally considered as a treatment option beyond curative intent [26]. However, the treatment option is frequently administered in real clinical practice when surgical or ablative procedures are infeasible, and several studies have reported comparable results to hepatic resection or radiofrequency ablation (RFA) [27-31]. Therefore, our institution provides TACE plus high-dose radiotherapy as a viable alternative treatment option for patients who are ineligible for hepatic resection or RFA [32]. With the above-mentioned reasons, in this study, we have regarded high-dose radiotherapy in addition to TACE as curative aim radiotherapy. Radiotherapy for management of symptomatic metastasis, and relief of portal vein thrombosis were regarded as palliative aim radiotherapy. Radiotherapy in initial management was defined as radiotherapy utilized within one month after registration. Radiotherapy during the early treatment process was defined as radiotherapy utilized within one year after registration.

The patients were categorized based on two factors: the age of the patients and the year of registration. First, patients were grouped as younger (<75 years) or elderly (≥75 years) or very elderly (≥80 years) based on their ages at the time of registration. Second, as the KLCA-NCC HCC practice guideline was updated in 2009, 2014, 2018, and 2022 [2,21-23], patients were categorized into three different groups based on the year of the practice guideline update: Period 1 (registered between 2005 and 2009), Period 2 (registered between 2010 and 2014), and Period 3 (registered between 2015 and 2017).

3. Statistical analysis

Variables are presented as medians with interquartile ranges or frequencies with percentages as appropriate. Differences in variables between the groups were compared using t-test or chi-square test. Overall survival (OS) was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons of the survivals were performed with the log-rank test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

1. HCC registry

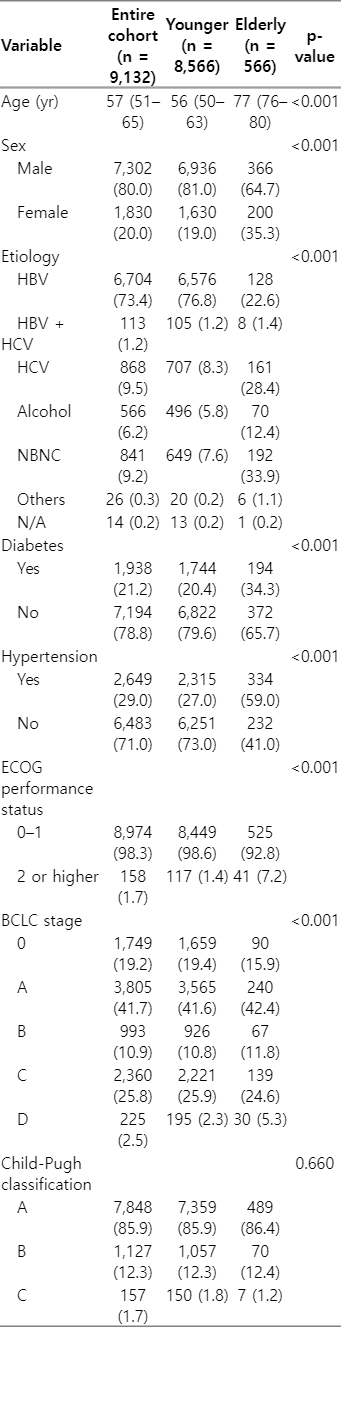

Among the 9,132 patients entered into the HCC registry during the study period, 8,566 (93.8%) were younger, 566 (6.2%) were elderly, and 152 (1.7%) were very elderly. Though the overall proportion of the elderly and very elderly was low, the incidence increased significantly throughout the study period: from 3.1% (18 patients) to 11.4% (91 patients) for the elderly and from 0.5% (3 patients) to 3.8% (30 patients) for the very elderly. The annually registered number of patients with HCC and the proportion of elderly and very elderly are illustrated in Fig. 1.

The annual number of patients who entered the HCC registry (yellow bar) and the proportion of elderly (blue solid line) and very elderly patients (red solid line). The trendlines of the proportion of the elderly and the very elderly are illustrated in dotted lines. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

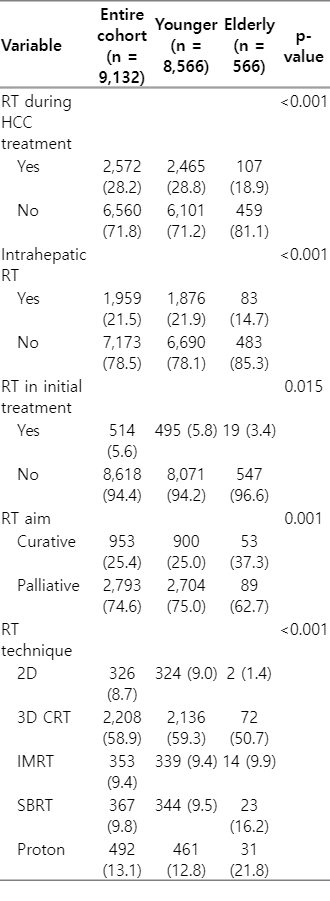

The patients’ clinical characteristics differed significantly between the age groups. The elderly patients had a significantly higher proportion of females, HCC with non-viral etiology, diabetes, hypertension, worse ECOG performance status, and high BCLC stage. Details of the clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

2. Radiotherapy in the HCC registry

In the subsequent HCC treatment process, 2,572 patients (28.2%) underwent 3,746 radiotherapy sessions, with 2,465 patients (28.8%) from the younger group undergoing 3,604 radiotherapy sessions and 107 patients (18.9%) from the elderly group undergoing 142 radiotherapy sessions. A significantly higher proportion of patients in the elderly group received radiotherapy with a curative aim with advanced radiotherapy techniques compared to the younger group. However, the proportion of patients receiving radiotherapy for intrahepatic lesion and radiotherapy in initial treatment was significantly lower for the elderly patients. Details of the radiotherapy are summarized in Table 2.

3. Radiotherapy trend of elderly patients in the HCC registry

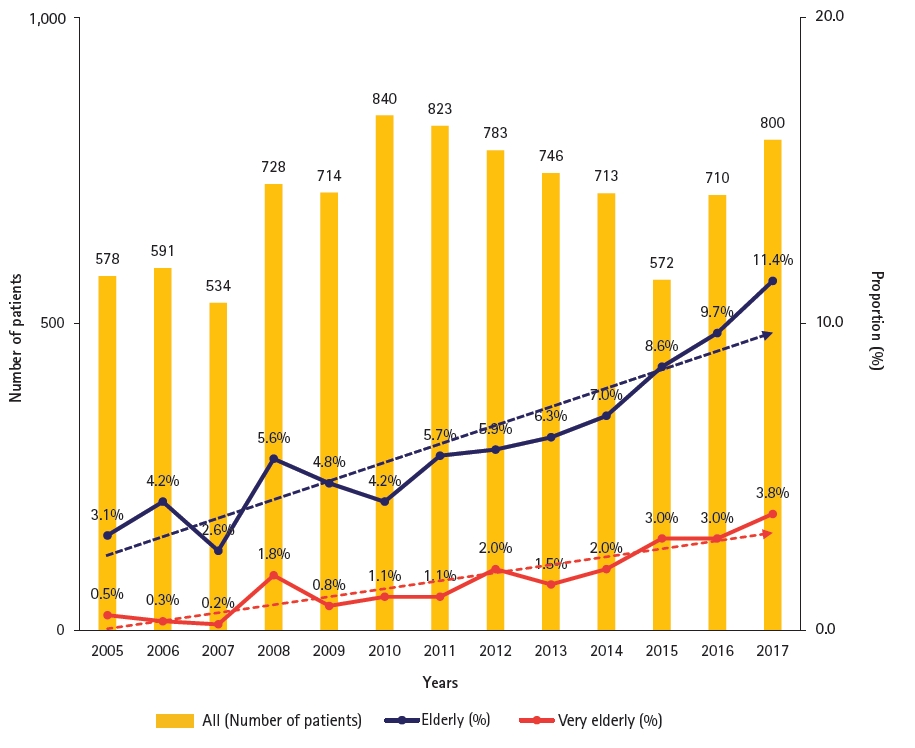

Fig. 2 illustrates the radiotherapy utilization rate over time with patients categorized based on age and the year of registration. The rates of the elderly group are shown in a solid line, and the rates of the younger group are shown in a dotted line. The radiotherapy utilization rate has gradually increased over time (red to orange to blue line) regardless of the age group. The overall utilization rate of the elderly group was lower than that of the younger group. However, the gap between the age groups has been narrowing over time. It was also to note that the radiotherapy utilization rate in the elderly is rapidly increasing in the early HCC treatment process, radiotherapy utilized within one year after registration, from 6.1% in Period 1 to 15.3% in Period 3. The utilization rates are summarized in Table 3.

Radiotherapy utilization rates of the different patient groups. The elderly groups are shown in solid lines and the younger groups are shown in dotted lines. Patients registered between 2005 and 2009 are categorized as Period 1 (red), between 2010 and 2014 as Period 2 (orange), and between 2015 and 2017 as Period 3 (blue).

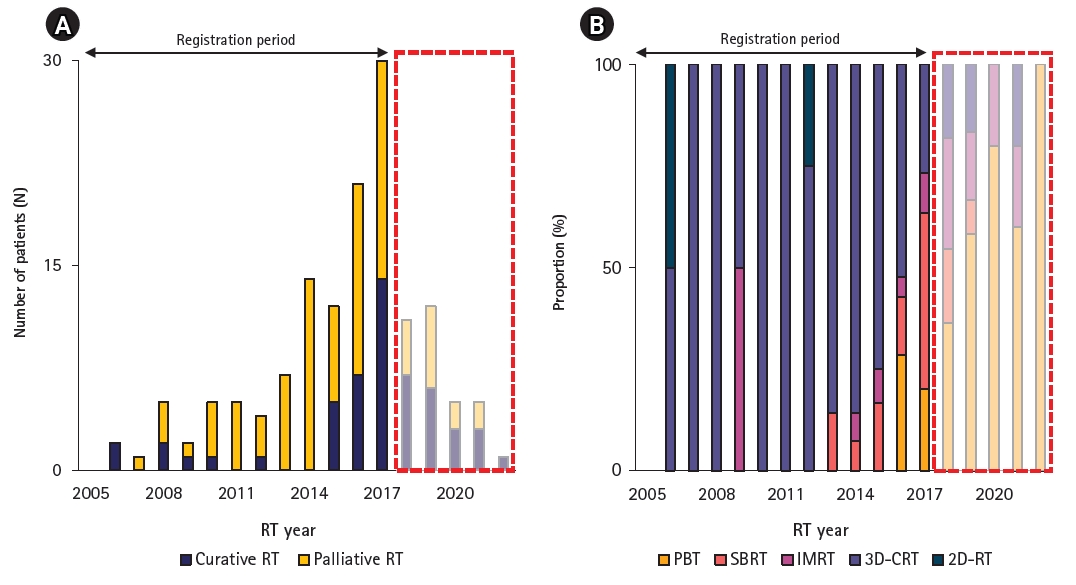

The trends of radiotherapy utilization in the elderly are illustrated in Fig. 3. The number of patients receiving radiotherapy (Fig. 3A) and the proportion of respective radiotherapy techniques (Fig. 3B) are shown based on the year of radiotherapy. Radiotherapy utilization in these elderly patients has increased overtime. While only two radiotherapy sessions were performed in 2006, 30 radiotherapy sessions were performed in 2017. After peak radiotherapy utilization was observed in 2017, the number of radiotherapy utilization gradually decreased afterwards due to the population of the current study. As this study is based on patients who entered HCC registry between 2006 and 2017, patients diagnosed after 2018 were not included, resulting in a decreased number of radiotherapy utilization after 2018. The proportion of patients receiving curative aim radiotherapy changed during the study period. While only 15.6% of radiotherapies in Periods 1 and 2 were curative aim (7 out of 45 radiotherapy sessions), 47.4% of radiotherapies in Period 3 and after were curative (46 out of 97 radiotherapy sessions). Utilized radiotherapy techniques have also changed dramatically during the study period. While all of the patients treated before 2008 were managed with either 2D-RT or 3D-CRT, more than two-thirds of the patients who underwent radiotherapy after 2017 were managed with advanced radiotherapy techniques, such as IMRT, SBRT, or PBT.

Radiotherapy utilization in elderly HCC registry patients. (A) The number of radiotherapies is shown in stacked column chart, with curative intent shown in blue bar and palliative intent shown in yellow bar. (B) The proportion of utilized radiotherapy techniques is shown as 100% stacked column chart. As this study is based on patients registered between 2005 and 2017, radiotherapies after 2018 are shown in a translucent box. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; RT, radiotherapy; PBT, proton beam therapy; SBRT, stereotactic body radiotherapy; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiotherapy; 3D CRT, three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy; 2D RT, two-dimensional radiotherapy.

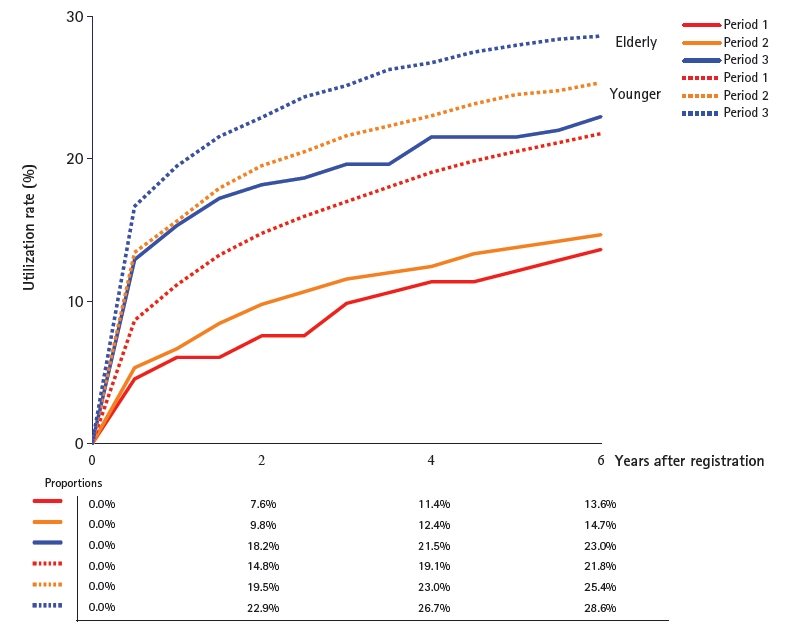

4. OS of elderly patients in HCC registry

The OS of the elderly patients in the HCC registry is illustrated in Fig. 4. Periods 1 and 2 did not differ significantly, with a respective 5-year OS of 33.6% and 30.2% (p = 0.991). However, OS significantly improved in Period 3 compared to the previous two groups, with a 5-year OS of 53.5% (Period 1 vs. 3, p < 0.001; Period 2 vs. 3, p = 0.011).

Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves of elderly patients in the HCC registry, categorized based on the year of registration. Patients registered between 2005 and 2009 are categorized as Period 1 (red), between 2010 and 2014 as Period 2 (orange), and between 2015 and 2017 as Period 3 (blue). HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

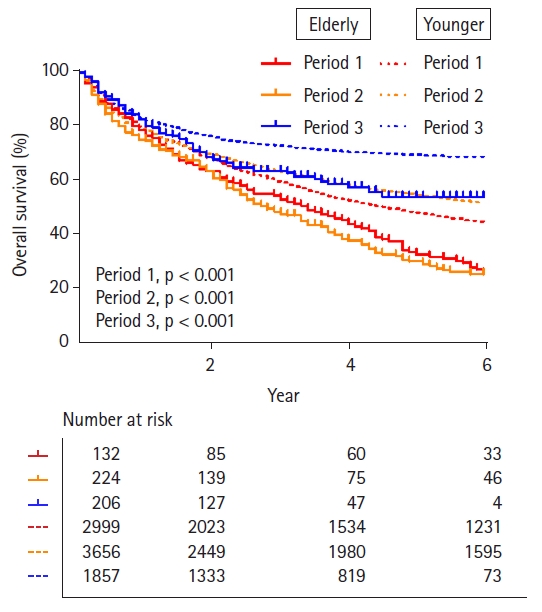

We also compared the OSs of the elderly and younger patients in the same registration period. As illustrated in Fig. 5, OS was significantly worse for elderly patients throughout the study period. The respective 5-year OSs were 33.6% versus 48.6% (p < 0.001) for Period 1, 30.2% versus 55.2% (p<0.001) for Period 2, and 53.5% versus 69.7% (p<0.001) for Period 3.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves of elderly and younger patients in the HCC registry, categorized based on the year of registration. The elderly groups are shown in solid line, and younger groups are shown in dotted line. Patients registered between 2005 and 2009 are categorized as Period 1 (red), between 2010 and 2014 as Period 2 (orange), and between 2015 and 2017 as Period 3 (blue). HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study shows the current trend of radiotherapy in the management of elderly patients with HCC in our institution. The proportion of these patients was continuously increasing. The radiotherapy utilization rate also increased during the study period, especially during the early HCC treatment process. The proportion of advanced radiotherapy techniques also increased over time. Our results demonstrate the changing role and increasing utilization of radiotherapy for the management of elderly HCC.

The reason for the increased proportion of radiotherapy utilization seems to be due to the following factors. Compared to the past, radiotherapy-related hepatic toxicity is better understood [10,11,33]. Based on the understandings and concrete evidences, liver constraints are becoming more detailed with consideration of radiation dose, fraction size, irradiated liver volume, and hepatic function [34,35]. The introduction of IMRT, SBRT, and particle beam radiotherapy, and improvements in image-guided radiotherapy has led to more precise and conformal radiotherapy available [17]. It has become possible to achieve the complex and tight dose constraints consistently, leading to widening the indications for radiotherapy, resulting in increasing trend of radiotherapy utilization for HCC.

Elderly patients with HCC are known to have several distinct characteristics compared to younger patients [5,36-38]. First, they are reported to have a higher proportion of female patients, due to longer life expectancy of women [39,40]. Second, the proportion of patients with HBV infection is lower, and HCV infection is higher for these patients [38]. Third, the proportion of patients with non-viral etiology is higher [38,41], which is likely to be associated with the increasing incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related HCC in elderly patients [42,43]. Our findings are in line with other previously reported studies: female (35.3% vs. 19.0%), HBV (22.6% vs. 76.8%), HCV (28.4% vs. 8.3%), NBNC (33.9% vs. 7.6%) (Table 1).

As shown in Fig. 5, there was significant OS difference between elderly and younger patients throughout the study period. Several factors may have influenced the survival differences. First, elderly patients usually have multiple comorbidities, representing a hard-to-manage, complex group of patients [9,44]. They are considered to be more vulnerable to treatment-related complications [6,37]. The elderly patients in current study had significantly higher proportion of comorbidities, and this could have led to worse survival of the elderly group (Table 1). Second, there are no clear prospective evidence or treatment guidelines for elderly patients with HCC currently. This may lead to the undertreatment of medically fit patients, and the overtreatment of medically unfit patients, affecting survival of the patients [9].

However, the role of radiotherapy in elderly patients with HCC is not fully established, and there are only a few retrospective studies available. Teraoka et al. [18] evaluated the safety and efficacy of SBRT for elderly patients with HCC. They compared clinical outcomes between the elderly group (aged 75 years or older) and the younger group (aged younger than 75 years) and reported that there was no statistically significant difference in clinical outcomes between the groups. Jang et al. [19] also investigated the role of SBRT for elderly patients with HCC. They retrospectively reviewed patients 75 years or older who underwent SBRT for HCC. The 5-year local tumor control rate was 90.1%, and OS was 40.7% with minimal treatment-related toxicity, which was comparable with the clinical outcomes in all age group [45]. Iwata et al. [20] investigated the efficacy and safety of image-guided PBT for elderly patients with HCC, aged 80 years or older. They report 2-year OS and local control of 88% and 76%, respectively. Toxicity was minimal with no reduction in quality of life during or after PBT. The results of the studies are summarized in Table 4. We also observed that though the OS of the elderly patients was worse compared to that of the younger patients, the OS of patients who received radiotherapy during the initial management was not different between the age groups (Fig. 5). The finding potentially indicates that radiotherapy in the management of elderly patients with HCC is as effective as in the management of younger patients with HCC. Taken together, radiotherapy for the elderly patients with HCC seems to be equally effective and safe as for the younger patients with HCC. However, the results should be taken with caution as the studies are retrospective in nature with relatively small sample sizes.

There were several limitations in this study. First, this study is based on registry data from a single institution in an HBV-endemic country. The patient population and treatment policy of our institution may not be identical to those of other institutions or countries. Second, we did not perform a qualitative analysis of radiotherapy, such as radiotherapy dose, treatment outcomes, or toxicity. Third, as the study population is the HCC registry patients registered between 2005 and 2017. The results may not accurately reflect how currently diagnosed patients are being treated. However, though the limitations, we believe that the current study adequately presents the changing trend of radiotherapy in the management of elderly patients with HCC in actual clinical practice.

In conclusion, there was a consistent trend in increased incidence and proportion of elderly patients with HCC during the study period. With the aid of advancements in radiotherapy techniques, the role and utilization of radiotherapy in the management of elderly patients with HCC has increased. The role of radiotherapy in the management of elderly HCC is expected to further increase in the future.

Notes

Statement of Ethics

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (No. 2021-12-093-001). Written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Park HC. Investigation and methodology, Park HC; Bae BK; Yu JI. Project administration, Park HC. Resources, Park HC; Bae BK; Yu JI. Supervision, Park HC. Writing of the original draft, Park HC; Bae BK. Writing of the review and editing, Park HC; Bae BK; Yu JI; Goh MJ; Paik YH. Formal analysis, Park HC; Bae BK; Yu JI. Data curation, Park HC; Bae BK; Yu JI; Goh MJ; Paik YH. Visualization, Park HC; Bae BK; Yu JI.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.