Current status and comparison of national health insurance systems for advanced radiation technologies in Korea and Japan

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to compare the current status of the national health insurance system (HIS) for advanced radiation technologies in Korea and Japan.Materials and methods: The data of the two nations were compared according to the 2019 guidelines on the application and methods of medical care benefit from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea and the 2020 medical fee points list set by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.

Results

Both countries have adopted the social insurance system and the general payment system which is fee-for-service for radiotherapy. However, for proton and carbon ion therapy, the Japanese system has adopted a bundled payment system. Copayment for radiotherapy is 5% in Korea and 30% (7–69 years old) in Japan, with a ceiling system. A noticeable difference is that additional charges for hypofractionation, tele-radiotherapy planning for an emergency, tumor motion-tracking, purchase price of an isotope, and image-guided radiotherapy are allowed for reimbursement in the Japanese system. There are some differences regarding the indication, qualification standards, and facility standards for intensity-modulated radiation therapy, stereotactic body radiation therapy, and proton therapy.

Conclusion

Patterns of cancer incidence, use of radiotherapy and infrastructure, and national HIS are very similar between Korea and Japan. However, there are some differences in health insurance management systems for advanced radiation technologies.

Introduction

Patterns of cancer incidence and the role of radiotherapy in cancer treatment are very similar between Korea and Japan [1,2]. While 45% to 55% of patients with cancer have access to a well-developed radiotherapy infrastructure in the Western countries, in Korea and Japan, 25% to 30% of cancer patients are treated with radiotherapy [3-5]. However, there are some differences and similarities in radiotherapy infrastructure and organization patterns between Korea and Japan. Radiotherapy infrastructure showed fragmentation in both nations with a mixed pattern of capital centralization and fragmentation in non-capital areas in Korea, while in Japan, it showed uniform regional distribution [6-8].

Characteristics of both nations’ universal health insurance system (HIS) are: (1) covering all citizens with social insurance, (2) easy access to medical institutions, and (3) high-quality medical services with low costs and have reached the world's highest level of life expectancy and met the healthcare standards [9,10]. However, there are some differences regarding the indication, qualification standards, and facility standards for reimbursement for advanced radiation technologies [11-13].

This study aimed to compare the characteristics and patterns of the HIS for advanced radiation technologies between Korea and Japan by focusing on technologies such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), and particle therapy.

Materials and Methods

We compared characteristics, patterns of the HIS, specific indications, and facility qualification for advanced radiation technologies between Korea and Japan, focusing on IMRT, SBRT, intracavitary radiotherapy (ICR), proton, and carbon ion therapy. Furthermore, we compared both nations’ data according to the 2019 guidelines on the application and methods of medical care benefit from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea and the 2020 medical fee points list set by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan [11-13]. As the cost of insurance treatment between the two countries varies greatly due to social and economic differences, simple comparison of treatment fee was excluded from this study.

Results

In Korea and Japan, healthcare service payment in radiotherapy is mainly based on a fee-for-service system. Both the Japanese health insurance system (JHIS) and the Korean health insurance system (KHIS) require the insured and dependents who receive healthcare services to pay copayment that is a part of total healthcare expenses. In KHIS, the copayment for cancer patients is 5% for all. Meanwhile, copayments in JHIS differ according to age and income status: 10% for 75 years or older (active income earner, 30%), 20% for 70 to 74 years (active income earner, 30%), 30% for 7 to 69 years, and 20% for 6 years or less, respectively. Patients (18 years or younger) with specific chronic pediatric diseases including cancer can be supported according to this income. For pediatric radiotherapy, additional treatment costs ranging from 20% to 80% are recognized depending on age in both systems (Table 1). Both have a copayment ceiling to adequately protect patients from catastrophic healthcare expenditures.

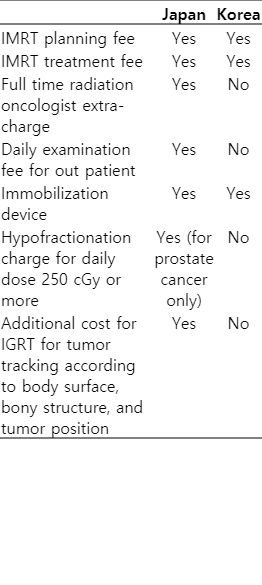

The maximum permissible radiotherapy sites and radiotherapy planning for reimbursement during a course of treatment are two in JHIS and three in KHIS, respectively. In JHIS, unlike in KHIS, additional charge for hypofractionation, tumor motion tracking, and IGRT are allowed. Recently, in JHIS, tele-radiotherapy planning for emergency treatment by other institutions has been allowed if there is a lack of suitable manpower (Table 2).

General comparison of national health insurance system for RT in cancer patients between Japan and Korea

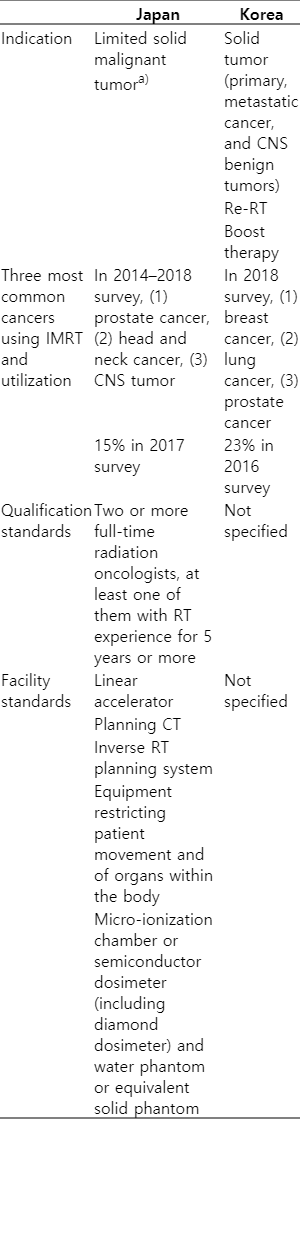

JHIS covers the cost of IMRT for only localized solid malignant tumors, while KHIS covers for metastatic lesions as well. In JHIS, the minimum conditions of IMRT using multi-leaf collimators are defined as follows: (1) more than three portals, (2) more than three intensity-modulated beams per portal, and (3) inverse planning. In JHIS, IMRT is reimbursed when the following personnel are present: (1) two full-time radiation oncologists and a radiotherapy technician, each with more than 5 years of radiotherapy experience and (2) an individual responsible solely for precision control of the radiotherapy devices, irradiation plan verification, and assistance with the irradiation plan (e.g., a radiotherapist or other technician). In KHIS, there are no specific qualifications and facility standards. In both systems, healthcare service payment in IMRT is mainly based on a fee-for-service system that consists of the cost of planning, treatment, and immobilization device. In JHIS, additional costs for hypofractionated IMRT (daily dose 250 cGy or more) for prostate cancer, and in IGRT costs for tumor tracking are allowed (Tables 3, 4).

Comparison of national health insurance system for IMRT utilization, and facility qualification between Japan and Korea

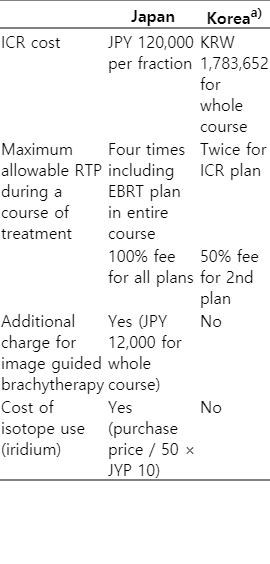

ICR treatment costs consist of the cost of each part of JHIS, but in KHIS, the cost for the entire treatment is ceilinged. In Korea, the total cost for 5 or more fractionations of ICR is the same. However, in JHIS, unlike in KHIS, extra-charge for image-guided planning and the purchase price of the isotope have been added to the cost of the treatment as one-time for the entire course of the high dose rate ICR (Table 5). Specific indications for SBRT covered by both countries are relatively similar regarding the organs. Oligo-metastases for SBRT is defined by five sites or less in both systems. General indication for tumor size for SBRT is defined by 5 cm or less in JHIS. The details have been presented in Table 6.

Comparison of national health insurance system for ICR for cervical cancer between Japan and Korea in 2020

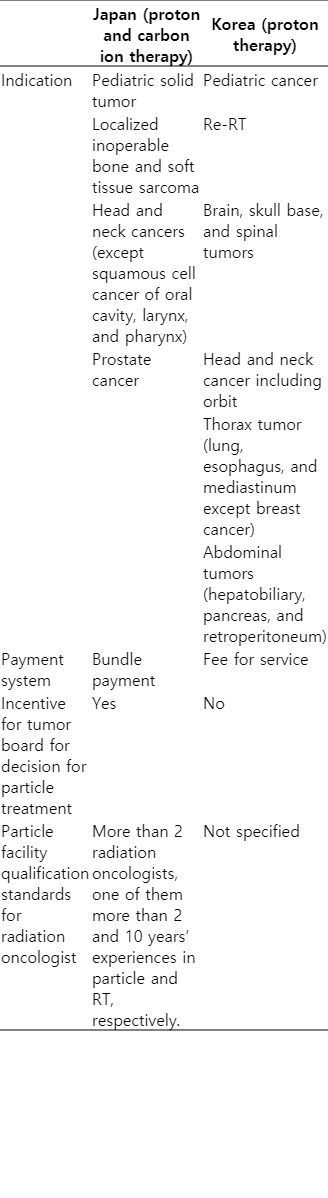

JHIS for proton and carbon ion therapy has been adopted as a bundle or package price. Proton therapy for pediatric solid tumor is covered by the HIS in both countries. However, there are some differences in specific indications and facility qualifications for proton therapy in both countries. In JHIS, indication for proton and carbon ion therapy covered by health insurance are defined as follows: (1) pediatric solid tumor; (2) localized inoperable bone and soft tissue sarcoma; (3) head and neck cancers (except squamous cell cancer of oral cavity, larynx, and pharynx); and (4) prostate cancer. However, KHIS has adopted a wider range of indications (Table 7). If the treatment decision for proton or carbon ion therapy is made through a multidisciplinary tumor board, then the additional treatment fee is recognized in JHIS.

Discussion and Conclusion

Both Japan and Korea have adopted the social insurance system which enables rapid and easy access to medical care with low cost for all citizens and meets the world’s highest level of life expectancy and healthcare standards. In countries adopting a tax-financed system, it is pointed out that citizens cannot choose a medical institution and waiting time to access medical care is generally long. For example, in the UK, general physicians (registered family physicians) are in charge of primary medical care. However, it is a problem as the waiting time is too long [9,10]. Fee-for-service payments are calculated by multiplying the price per score and resource-based relative value scores (RBRVS) based on the amount of work and resources such as manpower, facilities, equipment, and risks of medical treatments and the fee charged for each activity. The Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea determines RBRVS. In Japan, the medical service fees grading table is used to evaluate costs by grading individual technologies and services, determined by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare [11,12].

For the hypofractionated three-dimensional whole breast radiation (daily 2.5 Gy or more) instead of a conventional dose (46 to 50 Gy in 23 to 25 fractions), additional treatment cost is permitted in JHIS based on the randomized clinical results, which can reduce the number of hospital visits and the load on radiotherapy institutes [14]. In JHIS, tele-radiotherapy planning for emergency treatment is allowed if there is a lack of suitable manpower. This tele-radiotherapy planning for an emergency by another institution can be used to help with emergency treatment at poorly staffed treatment facilities.

The utilization rate of IMRT is steadily increasing. In Japan, it was 15% in 2017, while in Korea it was 23% in 2016 [15,16] (Table 3). There are some differences regarding the indication, qualifications, and facility standards for IMRT between two countries. JHIS covers the cost of IMRT for only localized solid malignant tumors, while KHIS covers for metastatic lesions as well. Oligo-metastasis may be considered as an indication for IMRT in KHIS. According to the Japanese Society for Radiation Oncology database report of 2018, IMRT was mostly used to treat prostate, head and neck, and central nervous system tumors in Japan [17]. However, in Korea, IMRT was most commonly used to treat breast, lung, and prostate cancers in 2018 [13].

JHIS adopted stricter indications for proton and carbon ion therapy (Table 7). Although the American Society for Radiation Oncology did not recommend proton therapy for prostate cancer outside of a prospective clinical trial, it is covered by JHIS [18]. However, in JHIS, the cost of proton therapy for prostate cancer is cheaper than other treatments and is set to be similar to the total cost of IMRT. If the treatment decision for proton or carbon ion therapy is made through a multi-disciplinary tumor board the additional treatment fee is recognized in Japan.

In conclusion, patterns of cancer incidence, infrastructure, and HIS are very similar between Korea and Japan. However, there is a considerable difference regarding the additional charges for hypofractionation, tumor motion tracking, and purchase price of an isotope among others. Furthermore, there are some differences regarding the indication, qualification standards, and facility standards for IMRT, SBRT, and proton therapy.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.